No, not those X-Files.

I'm talking about those interesting measurement stories where we were, like Mulder and Scully, desperately seeking a solution to a complicated problem. In our case, to measure variable X, and it was only through a combination of engineering, modeling, and lateral thinking like our heroes that we were able to measure our X—not directly, but in terms of a proxy measurement Y.

In an earlier article I introduced you to the idea of proxy measurements, and why they can, when appropriate, save you both time and money. Actually, it turns out that they are very appropriate—every client wants you to save time and money.

More seriously though, a clever proxy measurement can make the difference between having a product and not having one.

The Energy Problem in Rural India

Here's a neat real-world example.

The customer was a new startup targeting the large energy deficit in rural India. For all the usual reasons—poor infrastructure, insufficient generation, and inefficient revenue generation—there were few solutions. The biggest need for energy in this rural population was for household cooking fuel.

The startup, through extensive field work, realized that with careful customer selection, rethinking the technologies needed, and attention to the business model, a possible solution existed for at least one segment of the rural population.

The target: the small farmer with two or three cows on the farm.

About half of rural households own cattle. Cattle waste is often dried and used as fuel, but burning it is an inefficient way to generate energy. The idea was old—generate biogas—but the implementation was new. Instead of the traditional (and expensive) biogas fermenter, which requires cement, bricks, and extensive construction, the startup invented a pre-fabricated, flexible, PVC-coated fabric bag-based biogas plant.

Installing one required only two days: dig a shallow pit to hold the bag and set up a feed and waste overflow system. An integral part of the business model was commercializing the bio-fertilizer byproduct of the fermentation process. Generated gas was piped directly to the household stove.

Inside the house, the gas was filtered and pressurized with an inexpensive pump that generated the necessary pressure for the gas stove.

The Measurement Challenge

An important part of the economic model was the ability to measure the gas consumed by the cooking stove. The problem: there were no cheap enough and reliable enough pressure or flow sensors to meet the pricing constraints the startup needed to meet.

No "X" (gas consumption) measurement = No money.

The challenge was compounded. The problem wasn't just gas measurement that was required, but a mechanism to communicate weekly or monthly gas consumption back to the startup for billing. Cellular infrastructure was spotty at best. And when it was present, the combination of GPRS hardware and communication costs would further worsen the product budget.

Human-in-the-Loop IoT

My colleagues and I have long talked about building practical IoT systems and the design features and principles essential to success in building these kinds of systems, particularly in low-resource applications.

One key principle: it's not really the IoT (Internet of Things) but the IoPT (The Internet of People and Things).

For multiple reasons—cost, resilience, business models—people are fundamental components of a viable IoT system.

The Creative Solution: Proxy Measurements

Here are the "aha" moments that finally allowed us to meet our goals:

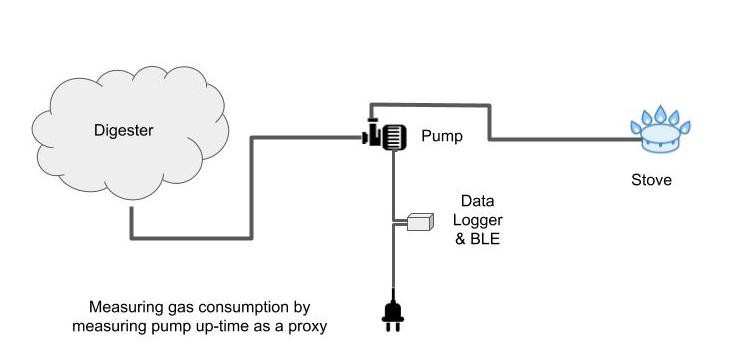

- Factory calibration: Since the components are all standardized, gas flow rates can be measured on the product at the factory. Only a one-time flow measurement needs to be taken. The pump provides a constant volume of gas at a nominal pressure head sufficient to operate the cooking stove.

- Proxy measurement: The amount of gas used under these conditions is directly related to the amount of time the pump is operating.

- Low-cost sensing: We can measure the amount of time the pump runs by simply connecting a low-cost data logger in line with the pump to measure cumulative operating time.

- Human channel: Since a field operative visits every couple of weeks to service the waste composter and take away the slurry, we have a communication channel back to headquarters.

- Mobile integration: A simple app on the field operative's phone retrieves the operating time from the data logger via BLE and resets it. This enables billing information to be collected and then aggregated back at the main service center.

System Architecture

And this is what the final system architecture looked like:

The Result

We ended up with:

- Low-cost gas consumption measurement capability

- A reliable way to capture data for billing purposes

- A process that, by using a human in the loop, provided a level of reliability that would have been hard to achieve with a more technical IoT solution

Key insight: In this case, our proxy measurement scheme yielded far more than just the value of "X"—it made a viable business model possible in a resource-constrained environment.

Further reading: Towards a Practical Architecture for Internet of Things: An India-centric View